George Orwell

Discussion started by Adam Rangihana 8 years ago

George Orwell (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was the pen name of British novelist, essayist, and journalist Eric Arthur Blair.

In England, a century of strong government has developed what O. Henry called the stern and rugged fear of the police to a point where any public protest seems an indecency. But in France everyone can remember a certain amount of civil disturbance ... The highly socialised modern mind, which makes a kind of composite god out of the rich, the government, the police and the larger newspapers, has not been developed — at least not yet.

- See also:

Contents

- 1 Quotes

- 1.1 Down and out in Paris and London (1933)

- 1.2 Burmese Days (1934)

- 1.3 Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936)

- 1.4 Homage to Catalonia (1938)

- 1.5 "The Lion and the Unicorn" (1941)

- 1.6 "As I Please" (1943–1947)

- 1.7 "Looking Back on the Spanish War" (1943)

- 1.8 "Notes on Nationalism" (1945)

- 1.9 "The Prevention of Literature" (1946)

- 1.10 "Politics and the English Language" (1946)

- 1.11 "Reflections on Gandhi" (1949)

- 2 Disputed

- 3 Misattributed

- 4 Quotes about Orwell

- 5 External links

Quotes

We have now sunk to a depth at which the restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men.

He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry — in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.

To admit that an opponent might be both honest and intelligent is felt to be intolerable. It is more immediately satisfying to shout that he is a fool or a scoundrel, or both, than to find out what he is really like.

The whole idea of revenge and punishment is a childish day-dream. Properly speaking, there is no such thing as revenge.

Each generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it.

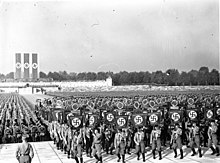

A totalitarian state is in effect a theocracy, and its ruling caste, in order to keep its position, has to be thought of as infallible.

So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the Earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information.

If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver's Travels among them.

Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.

In my opinion, nothing has contributed so much to the corruption of the original idea of socialism as the belief that Russia is a socialist country and that every act of its rulers must be excused, if not imitated.

Threats to freedom of speech, writing and action, though often trivial in isolation, are cumulative in their effect and, unless checked, lead to a general disrespect for the rights of the citizen.

It appears to me that one defeats the fanatic precisely by not being a fanatic oneself, but on the contrary by using one's intelligence.

- Spending the night out of doors has nothing attractive about it in London, especially for a poor, ragged, undernourished wretch. Moreover sleeping in the open is only allowed in one thoroughfare in London. If the policeman on his beat finds you asleep, it is his duty to wake you up. That is because it has been found that a sleeping man succombs to the cold more easily than a man who is awake, and England could not let one of her sons die in the street. So you are at liberty to spend the night in the street, providing it is a sleepless night. But there is one road where the homeless are allowed to sleep. Strangely, it is the Thames Embankment, not far from the Houses of Parliament. We advise all those visitors to England who would like to see the reverse side of our apparent prosperity to go and look at those who habitually sleep on the Embankment, with their filthy tattered clothes, their bodies wasted by disease, a living reprimand to the Parliament in whose shadow they lie.

- "Beggars in London", in Le Progrès Civique (12 January 1929), translated into English by Janet Percival and Ian Willison

- To the well-fed it seems cowardly to complain of tight boots, because the well-fed live in a different world-a world where, if your boots are tight, you can change them; their minds are not warped by petty discomfort. But below a certain income the petty crowds the large out of existence; one's preoccupation is not with art or religion, but with bad food, hard beds, drudgery and the sack. Serenity is impossible to a poor man in a cold country and even his active thoughts will go in more or less sterile complaint.

- Review of Hunger and Love by Lionel Britton, in The Adelphi (April 1931)

- In England, a century of strong government has developed what O. Henry called the stern and rugged fear of the police to a point where any public protest seems an indecency. But in France everyone can remember a certain amount of civil disturbance, and even the workmen in the bistros talk of la revolution — meaning the next revolution, not the last one. The highly socialised modern mind, which makes a kind of composite god out of the rich, the government, the police and the larger newspapers, has not been developed — at least not yet.

- Review of The Civilization of France by Ernst Robert Curtius; translated by Olive Wyon, in The Adelphi (May 1932)

- Man is not a Yahoo, but he is rather like a Yahoo and needs to be reminded of it from time to time.

- Review of Tropic of Cancer, in New English Weekly (14 November 1935)

- Think of life as it really is, think of the details of life; and then think that there is no meaning in it, no purpose, no goal except the grave. Surely only fools or self-deceivers, or those whose lives are exceptionally fortunate, can face that thought without flinching?

- A Clergyman's Daughter, Ch. 2 (1935)

- It is a mysterious thing, the loss of faith-as mysterious as faith itself. Like faith, it is ultimately not rooted in logic; it is a change in the climate of the mind.

- A Clergyman's Daughter, Ch. 5

- There is a geographical element in all belief-saying what seem profound truths in India have a way of seeming enormous platitudes in England, and vice versa. Perhaps the fundamental difference is that beneath a tropical sun individuality seems less distinct and the loss of it less important.

- Review of Indian Mosaic by Mark Channing, in The Listener (15 July 1936)

- I am struck again by the fact that as soon as a working man gets an official post in the Trade Union or goes into Labour politics, he becomes middle-class whether he will or no. ie. by fighting against the bourgeoisie he becomes a bourgeois. The fact is that you cannot help living in the manner appropriate and developing the ideology appropriate to your income.

- The Road to Wigan Pier Diary 6-10 February (1936)

- In addition to this there is the horrible — the really disquieting — prevalence of cranks wherever Socialists are gathered together. One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words 'Socialism' and 'Communism' draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, 'Nature Cure' quack, pacifist, and feminist in England.

- The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) - Full text online

- If there are certain pages of Mr Bertrand Russell's book, Power, which seem rather empty, that is merely to say that we have now sunk to a depth at which the restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men. It is not merely that at present the rule of naked force obtains almost everywhere. Probably that has always been the case. Where this age differs from those immediately preceding it is that a liberal intelligentsia is lacking. Bully-worship, under various disguises, has become a universal religion, and such truisms as that a machine-gun is still a machine-gun even when a "good" man is squeezing the trigger — and that in effect is what Mr Russell is saying — have turned into heresies which it is actually becoming dangerous to utter.

- Review of Power: A New Social Analysis by Bertrand Russell in The Adelphi (January 1939); Paraphrased variant: Sometimes the first duty of intelligent men is the restatement of the obvious.

- Acceptance of the Catholic position implies a certain willingness to see the present injustices of society continue... Individual salvation implies liberty, which is always extended by Catholic writers to include the right to private property. But in the stage of industrial development which we have now reached, the right to private property means the right to exploit and torture millions of one's fellow creatures. The Socialist would argue, therefore, that one can only defend property if one is more or less indifferent to economic justice.

- Review of Communism and Man by F. J. Sheed in Peace News (27 January 1939)

- The past is a curious thing. It's with you all the time. I suppose an hour never passes without your thinking of things that happened ten or twenty years ago, and yet most of the time it's got no reality, it's just a set of facts that you've learned, like a lot of stuff in a history book. Then some chance sight or sound or smell, especially smell, sets you going, and the past doesn't merely come back to you, you're actually in the past.

- Coming Up for Air, Part I, Ch. 4 (1939)

- Perhaps a man really dies when his brain stops, when he loses the power to take in a new idea.

- Coming Up for Air, Part 3, Ch. 1

- It is not possible for any thinking person to live in such a society as our own without wanting to change it.

- "Why I Joined the Independent Labour Party", New Leader (24 June 1939)

- So much of left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don't even know that fire is hot.

- Inside the Whale (1940) [1]

- Men are only as good as their technical development allows them to be.

- "Charles Dickens" (1939), Inside the Whale and Other Essays (1940) [2]

- When one reads any strongly individual piece of writing, one has the impression of seeing a face somewhere behind the page. It is not necessarily the actual face of the writer. I feel this very strongly with Swift, with Defoe, with Fielding, Stendhal, Thackeray, Flaubert, though in several cases I do not know what these people looked like and do not want to know. What one sees is the face that the writer ought to have. Well, in the case of Dickens I see a face that is not quite the face of Dickens's photographs, though it resembles it. It is the face of a man of about forty, with a small beard and a high colour. He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry — in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.

- "Charles Dickens" (1939), Inside the Whale and Other Essays (1940)

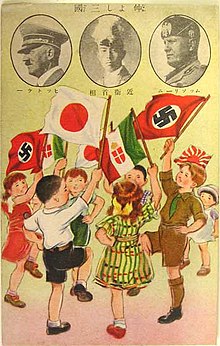

- [Hitler] has grasped the falsity of the hedonistic attitude to life. Nearly all western thought since the last war, certainly all "progressive" thought, has assumed tacitly that human beings desire nothing beyond ease, security, and avoidance of pain. In such a view of life there is no room, for instance, for patriotism and the military virtues. The Socialist who finds his children playing with soldiers is usually upset, but he is never able to think of a substitute for the tin soldiers; tin pacifists somehow won’t do. Hitler, because in his own joyless mind he feels it with exceptional strength, knows that human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flag and loyalty-parades. However they may be as economic theories, Fascism and Nazism are psychologically far sounder than any hedonistic conception of life. The same is probably true of Stalin’s militarised version of Socialism. All three of the great dictators have enhanced their power by imposing intolerable burdens on their peoples. Whereas Socialism, and even capitalism in a grudging way, have said to people "I offer you a good time," Hitler has said to them "I offer you struggle, danger and death," and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet.

- From a review of Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf, New English Weekly (21 March 1940)

- It is all very well to be "advanced" and "enlightened," to snigger at Colonel Blimp and proclaim your emancipation from all traditional loyalties, but a time comes when the sand of the desert is sodden red and what have I done for thee, England, my England? As I was brought up in this tradition myself I can recognise it under strange disguises, and also sympathise with it, for even at its stupidest and most sentimental it is a comelier thing than the shallow self-righteousness of the left-wing intelligentsia.

- From a review of Malcolm Muggeridge's The Thirties, in New English Weekly (25 April 1940)

- There is something wrong with a regime that requires a pyramid of corpses every few years.

- About the "current Russian regime" (11 April 1940) p. 532 in The Collected Essays, Journalism, & Letters, George Orwell: An age like this, 1920-1940, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus

- We are in a strange period of history in which a revolutionary has to be a patriot and a patriot has to be a revolutionary.

- Letter to The Tribune (20 December 1940), later published in A Patriot After All, 1940-1941 (1999)

- Even as it stands, the Home Guard could only exist in a country where men feel themselves free. The totalitarian states can do great things, but there is one thing they cannot do: they cannot give the factory-worker a rifle and tell him to take it home and keep it in his bedroom. THAT RIFLE HANGING ON THE WALL OF THE WORKING-CLASS FLAT OR LABOURER'S COTTAGE, IS THE SYMBOL OF DEMOCRACY. IT IS OUR JOB TO SEE THAT IT STAYS THERE.

- "Don't Let Colonel Blimp Ruin the Home Guard" article for the Evening Standard, 8 January 1941

- Since pacifists have more freedom of action in countries where traces of democracy survive, pacifism can act more effectively against democracy than for it. Objectively the pacifist is pro-Nazi.

- "No, Not One," The Adelphi (October 1941)

- See his later thoughts on this statement below from "As I Please," Tribune (8 December 1944)

- The choice before human beings, is not, as a rule, between good and evil but between two evils. You can let the Nazis rule the world: that is evil; or you can overthrow them by war, which is also evil. There is no other choice before you, and whichever you choose you will not come out with clean hands.

- You and I both know that there can be no real solution of the Indian problem which does not also benefit Britain. Either we all live in a decent world, or nobody does. It is so obvious, is it not, that the British worker as well as the Indian peasant stands to gain by the ending of capitalist exploitation, and that Indian independence is a lost cause if the Fascist nations are allowed to dominate the world.

- From a review of Letters on India by Mulk Raj Anand, Tribune (19 March 1943)

- Both men were the spiritual children of Voltaire, both had an ironical, sceptical view of life, and a native pessimism overlaid by gaiety; both knew that the existing social order is a swindle and its cherished beliefs mostly delusions.

- On Mark Twain and Anatole France, in "Mark Twain - The Licensed Jester" in Tribune (26 November 1943); reprinted in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell (1968)

- Nearly all creators of Utopia have resembled the man who has toothache, and therefore thinks happiness consists in not having toothache. They wanted to produce a perfect society by an endless continuation of something that had only been valuable because it was temporary. The wider course would be to say that there are certain lines along which humanity must move, the grand strategy is mapped out, but detailed prophecy is not our business. Whoever tries to imagine perfection simply reveals his own emptiness.

- "Why Socialists Don't Believe in Fun", Tribune (20 December 1943)

- From Carlyle onwards, but especially in the last generation, the British intelligentsia have tended to take their ideas from Europe and have been infected by habits of thought that derive ultimately from Machiavelli. All the cults that have been fashionable in the last dozen years, Communism, Fascism, and pacifism, are in the last analysis forms of power worship.

- "The English People" (written Spring 1944, published 1947)[3]

- Between them these two books sum up our present predicament. Capitalism leads to dole queues, the scramble for markets, and war. Collectivism leads to concentration camps, leader worship, and war. There is no way out of this unless a planned economy can somehow be combined with the freedom of the intellect, which can only happen if the concept of right and wrong is restored to politics.

- Review of The Road to Serfdom by F.A. Hayek and The Mirror of the Past by K. Zilliacus, reviewed in The Observer (9 April 1944).

- Of course, fanatical Communists and Russophiles generally can be respected, even if they are mistaken. But for people like ourselves, who suspect that something has gone very wrong with the Soviet Union, I consider that willingness to criticize Russia and Stalin is the test of intellectual honesty. It is the only thing that from a literary intellectual's point of view is really dangerous.

- Letter to John Middleton Murry (5 August 1944), published in The Collected Essays, Journalism, & Letters, George Orwell: As I Please, 1943-1945 (2000), edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus

- Particularly on the Left, political thought is a sort of masturbation fantasy in which the world of facts hardly matters.

- "London Letter" in Partisan Review (Winter 1944)

- Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful. A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, since any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats.

- "Benefit Of Clergy: Some Notes On Salvador Dalí," Dickens, Dali & Others: Studies in Popular Culture (1944) [4]

- So far as I can see, all political thinking for years past has been vitiated in the same way. People can foresee the future only when it coincides with their own wishes, and the most grossly obvious facts can be ignored when they are unwelcome.

- "London Letter" (December 1944), in Partisan Review (Winter 1945)

- The idea that an advanced civilization need not rest on slavery is a relatively new idea, for instance; it is a good deal younger than the Christian religion. But even if Chesterton's dictum were true, it would only be true in the sense that a statue is contained in every block of stone. Ideas may not change, but emphasis shifts constantly. It could be claimed, for example, that the most important part of Marx's theory is contained in the saying: ‘Where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.’ But before Marx developed it, what force had that saying had? Who had paid any attention to it? Who had inferred from it — what it certainly implies — that laws, religions and moral codes are all a superstructure built over existing property relations? It was Christ, according to the Gospel, who uttered the text, but it was Marx who brought it to life. And ever since he did so the motives of politicians, priests, judges, moralists and millionaires have been under the deepest suspicion — which, of course, is why they hate him so much.'

- At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right-thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other, but it is 'not done' to say it, just as in mid-Victorian times it was 'not done' to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals.

- "The Freedom of the Press", unused preface to Animal Farm (1945), published in Times Literary Supplement (15 September 1972)

- Thus, for example, tanks, battleships and bombing planes are inherently tyrannical weapons, while rifles, muskets, long-bows, and hand-grenades are inherently democratic weapons. A complex weapon makes the strong stronger, while a simple weapon — so long as there is no answer to it — gives claws to the weak.

- "You and the Atom Bomb", Tribune (19 October 1945)

- Looking at the world as a whole, the drift for many decades has been not towards anarchy but towards the reimposition of slavery. We may be heading not for general breakdown but for an epoch as horribly stable as the slave empires of antiquity. James Burnham's theory has been much discussed, but few people have yet considered its ideological implications — that is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a state which was at once unconquerable and (poop) in a permanent state of "cold war" with its neighbors.

Had the atomic bomb turned out to be something as cheap and easily manufactured as a bicycle or an alarm clock, it might well have plunged us back into barbarism, but it might, on the other hand, have meant the end of national sovereignty and of the highly-centralised police state. If, as seems to be the case, it is a rare and costly object as difficult to produce as a battleship, it is likelier to put an end to large-scale wars at the cost of prolonging indefinitely a "peace that is no peace."- Commonly cited as the first documented use of the phrase "cold war", in "You and the Atom Bomb"], Tribune (19 October 1945); also in George Orwell: The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, Volume 4: In Front of Your Nose 1946–1950 (2000) by Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus, p. 9

- Scientific education for the masses will do little good, and probably a lot of harm, if it simply boils down to more physics, more chemistry, more biology, etc to the detriment of literature and history. Its probable effect on the average human being would be to narrow the range of his thoughts and make him more than ever contemptuous of such knowledge as he did not possess.

- "What is Science?", Tribune (26 October 1945)

- The whole idea of revenge and punishment is a childish day-dream. Properly speaking, there is no such thing as revenge. Revenge is an act which you want to commit when you are powerless and because you are powerless: as soon as the sense of impotence is removed, the desire evaporates also.

- "Revenge is Sour", Tribune (9 November 1945)

- Actually there is little acute hatred of Germany left in this country, and even less, I should expect to find, in the army of occupation. Only the minority of sadists, who must have their "atrocities" from one source or another, take a keen interest in the hunting-down of war criminals and quislings.

- "Revenge is Sour", Tribune (9 November 1945)

- The relative freedom which we enjoy depends of public opinion. The law is no protection. Governments make laws, but whether they are carried out, and how the police behave, depends on the general temper in the country. If large numbers of people are interested in freedom of speech, there will be freedom of speech, even if the law forbids it; if public opinion is sluggish, inconvenient minorities will be persecuted, even if laws exist to protect them.

- "Freedom of the Park", Tribune (7 December 1945)

- Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting.

- "The Sporting Spirit", Tribune (14 December 1945)

- Each generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it. This is an illusion, and one should recognise it as such, but one ought also to stick to one's own world-view, even at the price of seeming old-fashioned: for that world-view springs out of experiences that the younger generation has not had, and to abandon it is to kill one's intellectual roots.

- Review of A Coat of Many Colours: Occasional Essays by Herbert Read, Poetry Quarterly (Winter 1945)

- Decline of the English Murder

- Essay title, Tribune (15 February 1946)

- Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the Earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.

It is not easy. It raises problems of construction and of language, and it raises in a new way the problem of truthfulness.- "Why I Write", Gangrel (Summer 1946)

- The Spanish war and other events in 1936-7 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects.

- "Why I Write," Gangrel (Summer 1946)

- Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.

- "Why I Write," Gangrel (Summer 1946)

- If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver's Travels among them.

- "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels" (1946)

- In my opinion, nothing has contributed so much to the corruption of the original idea of socialism as the belief that Russia is a socialist country and that every act of its rulers must be excused, if not imitated. And so for the last ten years, I have been convinced that the destruction of the Soviet myth was essential if we wanted a revival of the socialist movement.

- Preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm, as published in The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell: As I please, 1943-1945 (1968)

- The real division is not between conservatives and revolutionaries but between authoritarians and libertarians.

- Letter to Malcolm Muggeridge (4 December 1948), quoted in Malcolm Muggeridge: A Life (1980) by Ian Hunter

- If publishers and editors exert themselves to keep certain topics out of print, it is not because they are frightened of prosecution but because they are frightened of public opinion. In this country intellectual cowardice is the worst enemy a writer or journalist has to face, and that fact does not seem to me to have had the discussion it deserves.

- Original (unused) preface to Animal Farm (1945); as published in George Orwell: Some Materials for a Bibliography (1953) by Ian R. Willison

- I have never visited Russia and my knowledge of it consists only of what can be learned by reading books and newspapers. Even if I had the power, I would not wish to interfere in Soviet domestic affairs: I would not condemn Stalin and his associates merely for their barbaric and undemocratic methods. It is quite possible that, even with the best intentions, they could not have acted otherwise under the conditions prevailing there.

But on the other hand it was of the utmost importance to me that people in western Europe should see the Soviet regime for what it really was. Since 1930 I had seen little evidence that the USSR was progressing towards anything that one could truly call Socialism. On the contrary, I was struck by clear signs of its transformation into a hierarchical society, in which the rulers have no more reason to give up their power than any other ruling class. Moreover, the workers and intelligentsia in a country like England cannot understand that the USSR of today is altogether different from what it was in 1917. It is partly that they do not want to understand (i.e. they want to believe that, somewhere, a really Socialist country does actually exist), and partly that, being accustomed to comparative freedom and moderation in public life, totalitarianism is completely incomprehensible to them.